What Remains: Collage and Culture

There are innumerable ways to free the angel, to rearrange his pieces.

When Jo and I were seventeen we took over the Literary Magazine at our public high school. It had been called “Genesis” before, but we renamed it “Palimpsest.” Jo had come up with the idea and informed me: a palimpsest is a piece of physical writing material on which the original text has been erased to make room for later writing, but of which traces remain.

No matter what I’m writing, I’m always writing about the same thing, and I used to resent that. But I’ve come to understand writing as a collage— I find the scraps laid before me and I know there’s something beautiful there, I only have to assemble it. Michelangelo once said, “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” The titular character in Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat sits in an artist’s studio and ponders, “Was the angel painted on the triptych caught in the material, or was the material transformed?” There are innumerable ways to free the angel, to rearrange his pieces. Things I wrote when I was in high school resurface in my journal in my 20s, pulled forward from the back of my brain by some ghastly skeletal hand. Stephen King is quoted as saying that when he writes, “[the stories are] all just there for me. You just take it. Everything fits together like it existed before. I never think of stories as made things; I think of them as found things. As if you pull them out of the ground, and you just pick them up.”

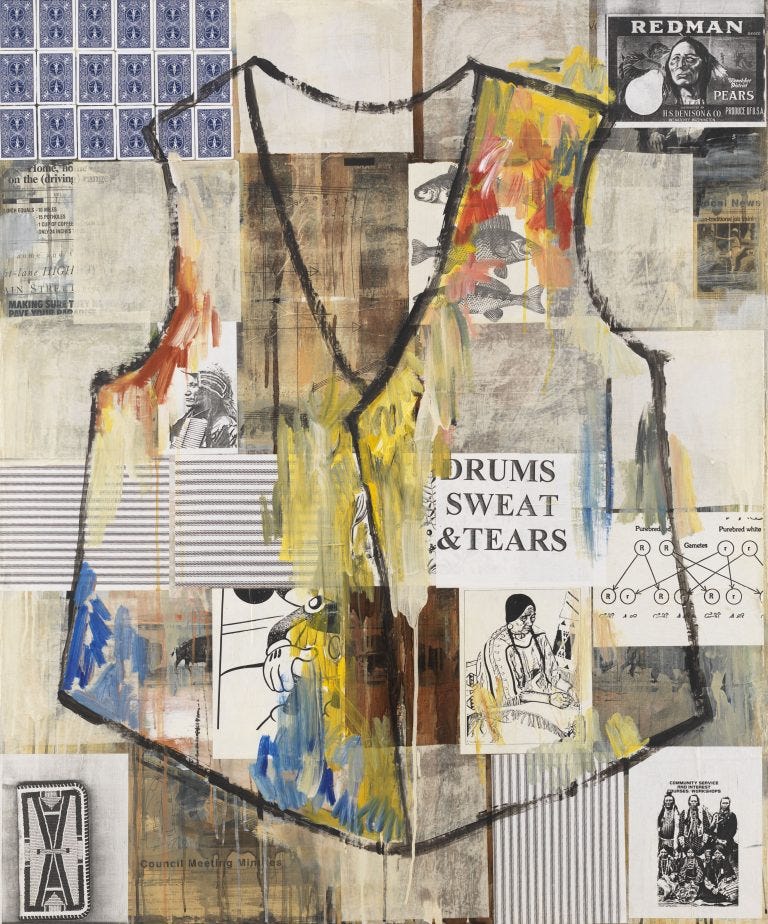

In visual art, an assemblage refers to a three dimensional composition made of everyday objects. The everyday component is essential— the materials are sometimes found, scavenged. The objects used are easily recognizable, but also take on a new identity in the context of the piece. In Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Flathead Vest (I See Red), a clip from a biology textbook illustrating the concept of dominant and recessive genes, something perhaps originally presented as “neutral” or “fact,” takes on a completely new meaning when juxtaposed with newspaper clippings demonstrating the indigenous struggle in the United States— blood quantum, phrenological anthropology. Even the title evokes this doubling affect— you might see a Flathead Vest, but I see red.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Flathead Vest (I See Red), 1996

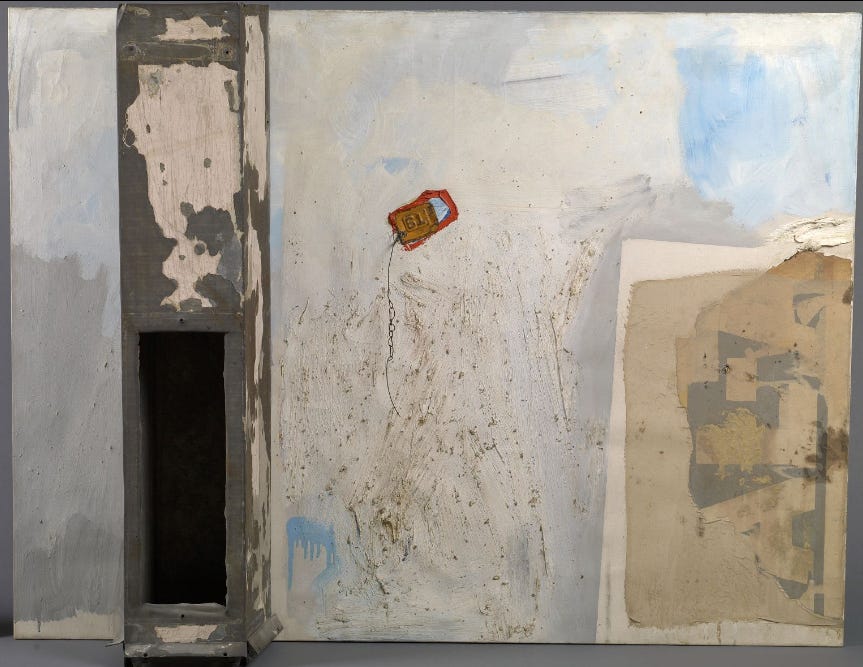

Robert Rauschenberg preferred to call his assemblages “combines.” At Colby, our museum had a piece that Rauschenberg made in 1962. I was assigned to write a paper about it, and I spent a long time staring into the gray void of the piece, trying to make sense of it. I didn’t dislike it, but it made me feel uncomfortable— the industrial metal tag dangling from the canvas, the scrap fabric applied unevenly, overlaid with what looked like grisly cement. I was frustrated that unlike many of Rauschenberg’s other combines, this one was Untitled, making the narrative of the piece seem all the more elusive, all the more predicated on the personal.

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, 1962

Roy Lichtenstein would take image appropriation a step further in his pieces. Rather than using common objects to trigger emotions and memories, Lichtenstein would actually appropriate scenes and iconography from popular culture. I always saw the inclusion of Mickey’s arm on the lower left of Quick-to-See Smith’s Flathead Vest (I See Red) as a nod to Lichtenstein’s Look Mickey and the history of the way Americans internalize popular culture. Lichtenstein proved that a cartoon mouse could conjure associations within us, no different than Duchamp’s use of a toilet in his readymade Fountain. You think of something when you see Mickey Mouse— watching princess movies at your first sleepover, an unfortunate trip to Disneyworld with your family. The art takes on these emotions, whether you want it to or not. And still, whether or not a work filled with allusions and re-appropriation is “actual art” remains highly debated.

Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey, 1961

In Jane Schoenbrun’s film I Saw The TV Glow, the final sequence shows the main character, Owen, cutting his chest open, revealing that where his heart should be, there is instead television static. Throughout the film, Owen grapples with whether his connection to popular culture is “real,” whether the emotions art makes him feel are actually coming from him or are manufactured. Early in the film, when a friend asks Owen about his sexuality, he says, “I think I just like TV shows.” Seeing ourselves in art and popular culture is often presented as identity-affirming, but I think it’s also dissociative, this idea that you might not exist if you don’t see yourself in this way.

Maggie Stiefvater’s new-adult series The Dreamer Trilogy depicts a world where some gifted individuals (”dreamers”) are capable of taking objects out of their dreams and into the real world. There are seemingly no limits on what can and cannot be taken— dreamers can conjure vehicles, weapons, mythical beasts, and even fully functional people with identities and thoughts of their own. But those people who have been dreamt need, essentially, magical talismans to keep them alive. The talismans need to have been created with great emotion behind them, and the most common are physical works of art. One character explains their power by saying:

“A man in Florence once had a heart attack when he saw the Birth of Venus… Palpitations are more common, though. That’s what Stendhal had. Couldn’t walk, he reported, after seeing a particularly moving work of art. And Jung! Jung decided it was too dangerous to visit Pompeii in his old age because the feeling— the feeling of all that art and history round him, it might kill him… Tourists in Jerusalem sometimes wrap themselves in hotel bedsheets. To become works of art themselves, you know? Part of history. A collective unconscious toga party.”

The series is mostly lighthearted and fun, but there is one line, spoken from someone who was dreamt, that rattles around in my head whenever I’m at an art museum or a cinema: “Imagine what this place would be if you did not have to beg at the feet of a painting for your life.” This, of course, is referring to a uniquely literal in-universe problem: the scarcity of charmed objects that keep the dreamt alive. And yet. I see myself between the lines of this fantasy novel. I look into a painted canvas and it acts as a mirror. And I wonder who I would be, how I would relate to others, without these reflections.

In Is There God After Prince, Peter Coviello’s sprawling book of low-culture critical essays, the author rejects the idea that media, even if we love it, is inherently valuable:

“The things we love may be startling, rapture-making, unraveling; their bare existence may at times feel to us like a living miracle, as much of grace as we are likely to encounter in our broken mortal span. I believe more or less all of this, as these essays gregariously attest. But none of it means these things do much for the world as such, beyond the small, small, small virtue of arming us with unaccustomed ways to think about it. This, I will continually insist, is not nothing. But it is awfully, awfully, awfully close.”

I love this quote. To me, art, even the “low” art that populates Tumblr and Instagram can be “startling, rapture-making, unraveling.” I think of the “corecore” movement on TikTok, where someone will transition a Tana Mongeau vlog into a clip from Succession, all while Twin Peaks music plays in the background. I can’t help but see shadows of Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein in these videos, when I write, when I tape old receipts into my journal. And all of this is important to me even if it means nothing at all— I started Substack because I needed a space to put the scenes from movies and television and YouTube that live in my head, the multi-media assemblage I’d see if I cut my own chest open. I hope you can see it too.